Hoppin’ Johns

Native to the South Carolina low country, Hoppin’ John is a classic Southern New Year’s dish, but where does the name come from, and why is eating it considered good luck? These questions have intrigued southerners, cooks and food historians for nearly two hundred years. The truth is that nobody really knows how this superstition began, but there are many theories, and this unique tradition shows no signs of fading.

Hoppin’ John is traditionally made with black-eyed or field peas, rice, and pork fat (like bacon), and served alongside greens. Black-eyed peas are a variety of cowpea, which were brought to the southern United States by enslaved West Africans, probably in the 18th century. Many of these Africans were specifically enslaved for their experience with rice cultivation in their native lands, where rice and bean dishes were common. So how did a crop—and probably a dish—imported from West Africa become a New Year’s tradition?

One important clue lies in the cultural role of the cowpea in the Senegambia region of Africa. In one essay from the book Rice and Beans, food historian Michael W. Twitty writes that the cowpea “stood as a symbol for divine protection, good fortune, and survival in times of hardship.” Likewise, as a food staple in West Africa, rice carried sacred connotations of its own. It’s not hard to understand how these associations accompanied the trans-Atlantic voyage and embedded themselves into southern American culture. And it’s not unreasonable to expect that good luck traditions manifest at the beginning of a new year, but there the historical record is unclear.

As for the name, there are a variety of folk etymologies, but the most widely accepted explanation is that it’s a corruption of the Haitian creole term for pigeon peas, pois a pigeon. Even though pigeon peas and cowpeas are different species, and the use of a French name is unexplained, this is the most common derivation.

Over the years, the good luck superstition surrounding Hoppin’ John has grown into some pretty interesting rituals, including these cited in the Dec. 28, 2008 edition of the Austin Chronicle:

“If you eat leftover Hoppin’ John the day after New Year’s Day, then the name changes to Skippin’ Jenny since one is demonstrating their determination of frugality. Eating a bowl of Skippin’ Jenny is believed to even better your chances for a prosperous New Year!” – Source: Beyond Black-Eyed Peas: New Year’s good-luck foods, by Mick Bann, Dec. 26,2008, Austin Chronicle.

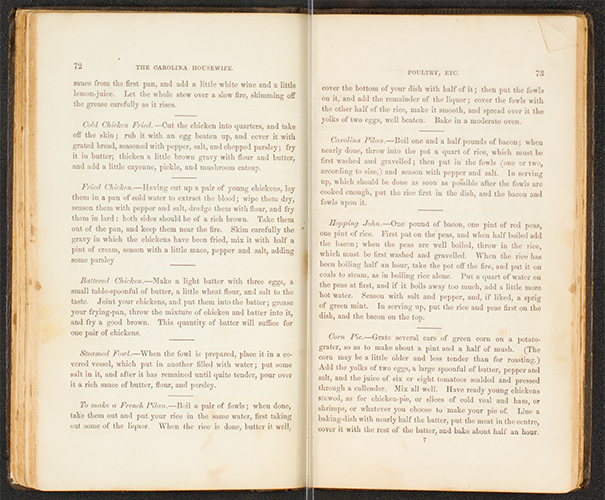

Although the dish itself was likely a hundred years older, the first recorded Hoppin’ John recipe is from the 1847 edition of The Carolina Housewife by Sarah Rutledge. The peas (in this case, red cowpeas), rice, bacon, and water are all thrown into one pot to cook, a technique originating in Africa. The basic ingredients haven’t changed in the many decades since, but it is common in modern Hoppin’ John recipes to see additional aromatics and the water replaced with chicken broth.

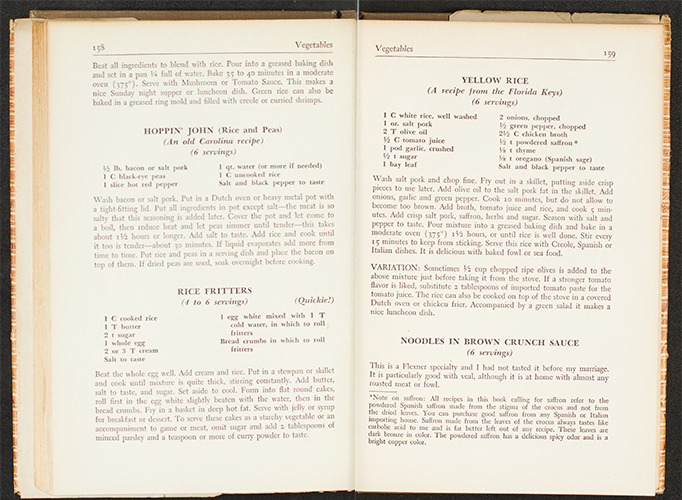

A somewhat more recent Hoppin’ John recipe is found in Marion Flexner’s 1949 Out of Kentucky Kitchens. Flexner, the mother of Vanderbilt professor emeritus John Flexner, was a prolific cookbook writer and expert on southern cooking. Her inclusion of this low country dish in a “Kentucky” cookbook is testament to its widespread popularity.

Flexner’s recipe is a simple one, using only bacon, black-eyed peas, red pepper, water, and rice. We have modified the directions a little from the original.

Hoppin’ Johns

Hoppin’ Johns

½ pound bacon

1 cup dried black-eye peas, soaked overnight

1 slice hot red pepper

1 quart water (or more if needed)

1 cup uncooked rice

Salt and Pepper

In a dutch oven, fry ½ pound of bacon over medium heat.

Add the black-eye peas, red pepper, and water to the pot.

Increase the heat to high bringing everything to a boil, then cover the pot with a lid, and reduce the heat to medium low.

Simmer for about 1 hour 30 minutes or until the beans are tender.

Add the rice, and simmer another 30 minutes or until it is tender.

Stir the rice occasionally so it does not stick to the bottom of the pot.

If the liquid evaporates, add more from time to time.

________________________________________________

Some related works from Vanderbilt Libraries and the History of Medicine Collection

A Lady of Charleston [Sarah Rutledge]. House and Home; or the Carolina Housewife. Charleston: John Russell, 1855.

Flexner, Marion. Out of Kentucky Kitchens. New York: Franklin Watts, 1949.

Hess, Karen. The Carolina Rice Kitchen: The African Connection. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1992

Jeffries, Bob. The Soul Food Cook Book. Indianapolis: Bobbs Merrill, 1969.

Paget, Russie H. Clemson House Cook Book: Carolina Up-Country Recipes. Charlotte: Heritage House, 1955.

Taylor, John Martin. Hoppin’ John’s Lowcountry Cooking. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2000.

Wilk, Richard R. and Livia Barbosa, editors. Rice and Beans: A Unique Dish in a Hundred Places. London: Berg, 2012.

Wilson, Ellen Gibson. A West African Cook Book. New York: M. Evans and Co., 1971.