Have you ever wondered what carolers are referring to when they sing: “Oh, bring us some figgy pudding?” You’ve probably heard of it (or its cousin, plum pudding) in English literature and nursery rhymes, too, but how is it made, what does it look like, and how is it different from American pudding?

Traditionally, “pudding” simply means dessert in the U.K. More specifically, an authentic English pudding consists of animal fat, dairy, eggs, bread, and other ingredients enclosed in cloth and then steamed or boiled. Although they’ve probably been around for many centuries, puddings were first attested in the 15th century as savory, sausage-like morsels, filled with bits of meat, grains, and fruit encased in animal intestines.

English cookbooks from the 1600s document an increasing variety of pudding recipes. Gervase Markham’s 1631 English Housewife lists white pudding (made with oats), hog’s liver pudding, bread pudding, rice pudding, and puddings made with calves’ entrails or hog’s blood. Several of these recipes also included dried fruits, such as dates, raisins, and currants.

By the early 18th century, cookbooks were beginning to show a slightly daintier approach to puddings. Eliza Smith’s Compleat Housewife (1737) still offered recipes for traditional black (“blood”) puddings and those made with animal casings, yet also included baked puddings made with oranges or apple, rosewater, and puff pastry. The transition toward sweet puddings is evident in a recipe in Smith’s book for “a good boiled pudding” that is made with suet, raisins, eggs, cream, brandy and flour, and boiled in a cloth sack instead of animal skins. With the addition of currants, this recipe became the basis for the plum and figgy puddings of the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Just as plum puddings weren’t made with plums, but rather raisins, the figs in figgy pudding were the result of a mistake by cookbook authors. In the local Cornish and Devonshire dialects, “fig” meant raisin, and so figgy puddings were originally just plum puddings by a different name. One distinguished Victorian, Isabella Beeton, took the reference literally, and when she published her extraordinarily popular Book of Household Management in the 1860s, and the recipe was changed forever by the introduction of figs to figgy pudding!

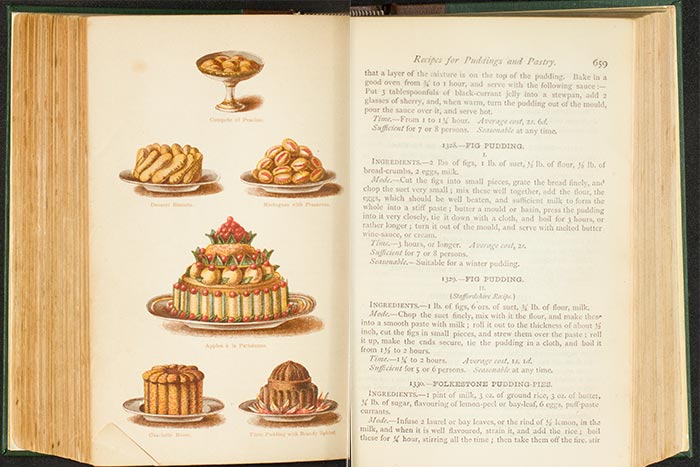

“2 lbs figs, 1 lb suet, 1/2 lb of flour, ½ lb of breadcrumbs, 2 eggs, milk”

“Cut the figs into small pieces, grate the bread finely, and chop the suet very small. Mix these very well together, add the flour, the egg which should be well beaten, and sufficient milk to form the whole into a stiff paste. Butter a mold or basin, press the pudding in very closely, tie it down with a cloth, and boil for 3 hours or longer.”

The Book of Household Management by Isabella Beeton, London, 1861

Mrs. Beeton’s recipe, just as Eliza Smith’s, included suet as one of its main ingredients. Suet is probably unfamiliar to most Americans, but it’s raw hard fat of beef or mutton, similar to lard, and it acted as the fat component in the pudding. Modern recipes call for butter as a replacement.

Traditionally Figgy Pudding was served warm with hard sauce, a sweet buttery glaze with brandy or rum, poured all over the top:

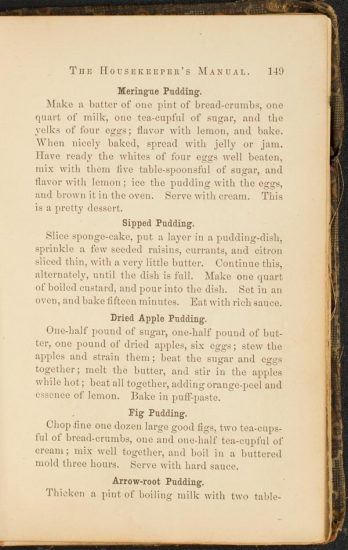

“Chop fine one dozen large good figs, two tea-cups-ful of breadcrumbs, one and one-half tea-cupful of cream, mix well together, and boil in a buttered mold three hours. Serve with hard sauce.” From The Housekeeper’s Manual: A Collection of Valuable Receipts, carefully selected and arranged by Moore Memorial Presbyterian Church, Nashville TN, 1875.

Modern boiled pudding recipes don’t stray far from their origins. For the most part, they still use the same basic ingredients: dried fruit, breadcrumbs, eggs, cream, and fat (butter or suet).

There have been many variations over the centuries, but the technique remains the same. Make a batter, spread it into a mold, and boil in a cloth for several hours. The cloth itself makes an appearance in a lovingly detailed description of the unveiling of the holiday pudding at the Cratchit’s house in Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol:

“Hallo! A great deal of steam! The pudding was out of the copper. A smell like a washing-day! That was the cloth. A smell like an eating-house and a pastrycook’s next door to each other, with a laundress’s next door to that! That was the pudding! In half a minute Mrs. Cratchit entered—flushed, but smiling proudly—with the pudding, like a speckled cannon-ball, so hard and firm, blazing in half of half-a-quartern of ignited brandy, and bedight with Christmas holly stuck into the top.”

The recipe below is the result of research among the cookbooks in Vanderbilt’s History of Medicine Collections. Looking over several recipes we noticed the ratios were the same across the board. Equal parts dried fruit, breadcrumbs, flour and cream. We have tested the recipe and you have the word of many librarians that it is tasty!

We used simple ingredients to stay as true to the original puddings as possible. Please enjoy simple Figgy Pudding, a recipe you can try at home.

Figgy Pudding with Hard Sauce:

(You will need a traditional pudding mold or a bundt pan that will fit into a 9×13 pan.)

Figgy Pudding:

1 ½ cup milk

1 ½ cup dried figs

1 ½ cup white whole wheat or all purpose flour

1 ½ cup breadcrumbs

1 cup white sugar

1 teaspoon cinnamon

1 teaspoon nutmeg

1 teaspoon salt

3 eggs, beaten

½ cup butter, melted

2-4 cups of water

Grease your pudding mold or bundt pan thoroughly.

Pour the milk and figs into a small pot and warm through over low heat for 10-15 minutes.

Preheat the oven to 350 degrees.

Stir together the flour, breadcrumbs, sugar, cinnamon, nutmeg, and salt.

Stir the beaten eggs into the dry ingredient mixture, then add the milk and fig mixture, and the butter until all of the ingredients are well blended.

Spread the batter into your pudding mold or bundt pan evenly, and cover the top with aluminum foil.

Place the pudding mold or bundt into the 9×13 pan, and pour 2-4 cups of water into the 9×13 pan (you want your mold to be sitting in about 1 ½ to 2 inches of water).

Carefully place the 9×13 pan with the mold or bundt pan sitting in water into the preheated oven.

Bake for 1 hour 45 minutes to 2 hours. The pudding should be firm to the touch.

(Be careful when uncovering the aluminum because hot steam will come out.)

Hard Sauce:

½ cup butter (a stick)

½ cup sugar

2 teaspoons bourbon (sub vanilla extract)

Sprinkle of nutmeg

Beat the butter, sugar, bourbon, and nutmeg with a mixer until smooth. Serve on top of the warm pudding.

The following books from Vanderbilt University Libraries’ History of Medicine Collections were consulted for this post:

Acton, Eliza. Modern Cookery, in all its Branches. London: Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans, 1851.

Armstrong, John. The Young Woman’s Guide to Virtue, Economy, and Happiness. Newcastle upon Tyne: McKenzie and Dent, 1817.

Beeton, Isabella. The Book of Household Management. London: Ward, Lock, 1878.

Coghan, Thomas. The Haven of Health. London: Anne Griffin for Roger Ball, 1636.

Collingwood, Francis and John Woollams. The Universal Cook, and City and County Housekeeper. London: R. Noble for J. Scatcherd, 1797.

Farley, John. The London Art of Cookery and Housekeeper’s Complete Assistant. London: John Fielding, 1783.

Glasse, Hannah. The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy. London: W. Strahan, 1784.

Kettilby, Mary. A Collection of above Three Hundred Receipts in Cookery, Physick and Surgery. London: Printed for the Executrix of Mary Kettilby, 1746.

Markham, Gervase. The English House-wife: Containing the Inward and Outward Vertues which Ought to Be in a Compleate Woman. London: Printed by Nicholas Okes for J. Harison, 1631.

Mason, Charlotte. The Lady’s Assistant for Regulating and Supplying the Table. London: Printed for J. Walter, 1793.

Moore Memorial Presbyterian Church. The Housekeeper’s Manual: A Collection of Valuable Receipts, Carefully Selected and Arranged. Nashville: Publishing House of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, 1875.

Smith, Eliza. The Compleat Housewife, or Accomplish’d Gentlewoman’s Companion. London: J. and J. Pemberton, 1737.

W.M. The Queens Closet Opened. London: Printed for Obadia Blagrave, 1783.

Woolley, Hannah. The Queen-Like Closet, or Rich Cabinet. London: Printed for R. Lowndes, 1672.

___________________________________

Writing – original draft, Recipe Developer, and Photographer: Leanna Myers, Web Designer and Social Media Coordinator at Vanderbilt Libraries

Writing – review & editing: Christopher Ryland, Curator of History of Medicine Collections at Vanderbilt Libraries

Supervision: Celia Walker, Associate University Librarian