Vanderbilt University Fine Arts Gallery intern Echo Sun (class of 2020) has put together a vibrant presentation of Japanese woodblock prints from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, now on view in Cohen Memorial Hall. Presented in conjunction with the Gallery’s current exhibition Then & Now: Five Centuries of Woodcuts, this display of work from Vanderbilt University’s collection reveals the enduring influence of traditional woodblock motifs, such as ukiyo-e (pictures of the “floating world”) prints, while highlighting examples of more contemporary, artist-driven expressions of the form. This companion presentation includes editions by Katsushika Hokusai, Utagawa Hiroshige, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, Kiyoshi Saito, and Takahashi Hiroaki (Shotei), among other Japanese artists working in the woodblock print medium over these two centuries.

Woodblock printmaking, or moku-hanga (木版画,) has a history in Japan dating back to the seventeenth century. The technique of woodblock printing is known for its use in ukiyo-e (浮世絵), or “pictures of the floating world” in the Edo Period (1603–1868), but it was also used in book publishing. Originating in China, Japanese moku-hanga printers exclusively used carved woodblocks instead of metal plates or lithographic stones prevalent in western printmaking. Although as the companion exhibition reveals, there is a long, deep history of the woodcut outside of Asia. Japanese printers used water-based inks, as opposed to the western oil-based ones. This approach enabled artists to create images with vibrant colors, delicate contours, and smooth color gradients.

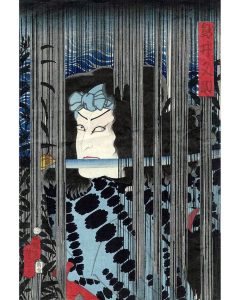

Ukiyo-e prints were produced in the Edo period as popular culture merchandise. They featured beautiful women (bijin-ga; 美人画), Kabuki actors (yakusha-e; 役者絵), folk tales, and scenes of famous places (meisho-e; 名所絵). The production of ukiyo-e prints involved a team of artisans: A publisher would commission an artist to draw a design, which would then be transferred to multiple woodblocks by the carver. One block, called the key block, would be inked by the printer using sumi (墨; black ink ), with subsequent blocks each separately inked with color, water-based vegetable and mineral pigments—a block for each color. Normally, only the publisher and the artist would be credited for the prints, which would be produced in hundreds, if not thousands, of copies to be sold in markets.

Although ukiyo-e prints were extremely popular in the Edo Period, Japanese art connoisseurs often viewed them as mere mass-productions, not fine art. As the Tokugawa government opened the door to the west in the mid nineteenth century, Japanese artists started to favor Western art-making techniques over traditional ones, in some instances regarding woodblock printing as primitive in comparison. The decline of ukiyo-e was inevitable, despite an effort to revitalize traditional printmaking by the last great master of this genre, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (月岡芳年; 1839–1892). Ironically enough, Western connoisseurs developed an immense interest in ukiyo-e, and started to import prints from Japan, while greatly influencing European artists such as Édouard Manet and Vincent Van Gogh, among many others.

The Shin-hanga (新版画;”new prints”) movement, begun in the early twentieth century, adhered to the traditional collaborative approach found within ukiyo-e workshops. However Shin-hanga artists incorporated Western techniques such as linear and atmospheric perspective with traditional subjects such as landscapes. The term shin-hanga was coined by Watanabe Shōzaburō (渡辺庄三郎; 1885–1962) in 1915, the major publisher of this genre of prints, aiming to distinguish the new prints from the traditional commercial objects, although the prints were mostly exported to the United States.

While Shin-hanga artists clearly linked their practice to the ukiyo-e tradition, many Japanese artists strove to produce work that emphasized self-direction in the production process, making works that were “self-drawn”(jiga; 自画), “self-carved”(jikoku; 自刻), and “self-printed”(jizuri; 自刷). A movement, also born in the twentieth century, referred to as sōsaku-hanga (創作版画; “creative prints”) emerged. In 1904, Yamamoto Kanae (山本鼎; 1882-1947) produced the first work designed, carved, and printed by the artist himself, marking the beginning of this movement.

The past lives in the present. Although the traditional ukiyo-e was dead, the art of woodblock printing is still burgeoning, emerging into new forms as in the case of sōsaku-hanga and shin-hanga. Japanese woodblock prints comprise a vital oeuvre of contemporary art, stemming from the old Edo tradition.

(Above text by Echo Sun, Vanderbilt University Fine Arts Gallery Intern, 2018–2019, Majoring in Art and Psychology, Class of 2020)